= For many politics is

something that is overheard =

‘I DO NOT BELIEVE THAT

THE REAL LIFE OF THIS

NATION IS TO BE FOUND EITHER IN THE

GREAT LUXURY

HOTELS AND THE PETTY GOSSIP OF

SO CALLED

FASHIONABLE SUBURBS,

OR IN THE OFFICIALDOM OF

ORGANISED MASSES.

IT IS TO BE FOUND IN THE HOMES OF

PEOPLE WHO ARE NAMELESS AND UNADVERTISED AND WHO,

WHATEVER THEIR INDIVIDUAL RELIGIOUS

CONVICTION OR

DOGMA, SEE IN THEIR CHILDREN THEIR GREATEST

CONTRIBUTION TO THE IMMORTALITY OF THEIR RACE’.

THOSE WORDS ARE IN SUBSTANCE AS TRUE TODAY AS THEY

WERE THEN.

(JOHN HOWARD, QUOTING ROBERT MENZIES,1997)

A by-no-means complete survey of Alice Springs monuments, from the grandiose to the banal

Located at the Alice Springs RSL club. Very poetic, but there's no sea in Alice Springs!

Typical, modest plaque-on-rock memorial. To Scott, struck down by lightning.

Central Australian Pioneer's Memorial

MORE LOVE HOURS THAN CAN EVER BE REPAID AND THE WAGES OF SIN.

Fans' spontaneous memorial to LA artist Mike Kelley.

(There is nothing fundamentally passive or superficial in overhearing the political)

Captain Cook chased a chook

All Around Australia

When he got back he got a smack

For Being A Naughty Sailor

Counter Monuments and Monument Building in Australia.

Click here for full PDF =

“The picture was clipped from a newspaper so carelessly the caption is missing. It shows a monument of a man on a horse, atop a tall granite pedestal. The rider, a figure of herculean build, is seated comfortably in the saddle, his left hand resting on its horn, his right pointing to something ahead (probably the future). A rope is tied around the neck of the rider, and a similar rope around that of his mount. In the square at the base of the monument stand groups of men pulling on the two lines. All this is taking place in a thronged plaza, with the crowd watching as the men tugging on the ropes strain against the resistance of the massive bronze statue.

The photograph captures the very moment when the ropes are stretched tight as piano wires and the rider and his mount are just tilting to the side—an instant before they crash to earth. We can’t help wondering if these men pulling ropes with so much effort and self-denial will be able to jump out of the way, especially since the gawkers crowded into the plaza have left them little room. This photograph shows the pulling down of a monument to one of the Shahs (father or son) in Teheran or some other Iranian city. It is hard to be sure about the year the photograph was taken, since the monuments of both Pahlavis were pulled down several times, whenever the occasion presented itself to the people. “

[ memory imposed on a landscape ]

( those occasions where the official frame is dismantled by rival images)

[ Aleppo Pine ]

= Dissonant Heritage =

The thing to occupy is media time; the way to do it is to take space. If an assembly gathered and nobody noticed, did it make a sound?

Elite Memory vs. Popular Memory

+ Surprising afterlives which transform original meanings +

( Between the discourse that comes before and the discourse that comes after )

“The Central Australian Pioneers Memorial was erected in 1955 to the memory of John Ross and all pioneers of Central Australia. Also known as the John Ross Memorial, the memorial was restored in 1994 and is now contained in a metal cage. The plaques are very difficult to read and photograph. There is some graffiti on the memorial. The “John Ross Memorial Fund” was commenced with the modest sum of £26 in the bank. John Ross was Central Australia’s first explorer-pioneer, and it is therefore only right that the fund should be in his name. Both he and his small son, Alexander, aged 10, made a hazardous journey right into Central Australia in search of fresh pastures as early as 1868-9. It is a story that would thrill any Australian school boy. John Ross was also the explorer, who discovered the Alice Springs (on March 17, 1871). Immediately after him came the surveyors and constructors of the, Overland Telegraph Line. These, men constitute our very first pioneers."

Click here for more text.

- Banal Nationalism = virtue, mateship, resilience, loss, hard work -

Ahok’s Flower Boards

Recently, floral tributes have appeared in their thousands

around Jakarta’s city hall as a sort of memorial to/

celebration of the city’s outgoing mayor Ahok. The photogenic

flower boards have since become a media sensation, with their

mediated form being distributed extensively within and outside

of Indonesia. Littered with references to popular culture, the

flower boards’ playful expressions coalesce (one of many

competing) undercurrents of life and politics in Indonesia.

Standing in for the bodies of their owners, the flower boards project this undercurrent onto the Indonesian media landscape, enshrining their interpretation of Ahok’s controversial fall from grace and power as a tragedy.

They are a very visible expression of certain popular tendencies suddenly and unpredictably coming together. Who first decided to dedicate a flower board to Ahok? How did others see it and decide to

follow suit? Or did many people spontaneously decide on the same gesture? At what point did the gesture take hold and feed off its circulation via social/ mainstream media? What do the flower boards say about the modern polity that is Jakarta and Indonesia?

How does a memorial like this differ in tone and in

how it affects an audience compared to more structured, state

planned ceremonies and acknowledgements? In their very

photogenicness, melancholy, and playfulness, are the flower

boards the ultimate solipsistic political gesture, occupying

media time but saying very little? Did the workers who burnt

flower boards on May Day, spontaneously riffing off the

affective charge of the flower boards (and also receiving

plenty of media time), make a similarly empty statement?

(What hits a person encountering the dissemination of news about power has nothing to do with how thorough or cultivated their knowledge is or how they integrate the imapact into their living)

Althusser’s View of How History is Made:

The rain of life pitter-patters down in the void of pre-history, before the beginning of time and space, steadily it falls, raining atoms, the dance of atoms. Everything falls, atoms in parallel with one another. Atoms rain as bodies falling through empty space, straight down, under their own weight. They fall, unconnected from one another, blind to one another, restricted from one another.

They

fall,

fall,

fall,

until, they

swerve;

something intervenes, something contingent breaks the parallelism, so small that it is hardly noticeable.

And yet, it alters the whole course of history, because in some, almost-negligible way, the swerve induces the encounter: one atom of rain encounters other atoms; vertical falling rain crisscrosses with other drops of falling rain; they connect and rain into one another, strike one another, encounter one another, pile up with one another.

Just enough of a swerve for you to call it a change of course.

Afghan Cameleers Monument, Alice Springs

The Prime Minister is touring the battlefields of France where his father and grandfather fought, carrying with him one of their wartime diaries. Is such wallowing in the past healthy? Sounds like black armband travel to me.

— Lucashenko, 2002

November 11th 2000, - Villers de Brenoux, France

Bleary eyed I turned over as the marching below reminded me of the coming dawn. Pull out, digger! The dogs are pissing on your swag. Treading khaki, clutching grandpop’s diary looking up at the bold granite, the wife at my side, the last trumpet notes ringing out.

“No place on earth has been more densely sown with Australian sacrifice than these fields in France”, I whispered to Janine. (She didn’t hear me.)

A SELECTION FROM JOHN HOWARD’S GRAND MEMORIAL TOUR DIARY, 2002

Defaced / Removed Confederate Statue

Bringing the angry god out of hiding: Defacing Money

Did John Reid know of the laws about defacing money before he cut up the several thousands of dollars he received from selling his treasured plot of real estate on the south coast, eighth wonder of the world, so as to begin, in 1982, a collage about the plight of political prisoners in Latin America?

In 1984, by which time Reid has cut up twenty-five hundred bills, mainly denominations of one, five, and twenty dollars, a colleague anonymously sent the Fraud Squad of the Australian Federal Police fifty two of the cut-up bills, with Reid’s name attached as evidence.

On the wall of Reid’s studio the police discovered the unfinished figure of a larger-than-life naked woman, spread-eagled on her back, being beaten by clubs. Below lay the artist’s raw materials: cups containing

squares, rectangles,

and crescent-shaped pieces of money,

sorted according to

shape and colour;

Australian paper money comes in gorgeous colours,

like monopoly money,

the colours

varying in intensity across the bill,

perfect for flesh tones,

bruises, and wounds.

Some bills had the Queen’s face carefully cut out in sweeping semicircles, leaving mysterious dark spaces between coiffured hair on one side, and the Australian coat of arms, held by a kangaroo and an emu, on the other.

Hardened fraud-dicks that they were, the police nevertheless were aghast.They returned with tweezers, gloves, plastic bags, and a forensic photographer to arrest Reid,under a 1959 law, on fifty-five counts of willfully mutilating Australian bank notes in his studio in the Canberra School of Art in the Australian National University.

_______________

He was the only statue of an Aboriginal in all of Perth, it seemed to me,and he was hidden away on Herrisson Island as though you wadgulas was ashamed of him. Some bastards stole his spear and, once, he was painted white as well. Often some wit would put an empty beer can in his hand or by his feet so he looked like nothing but a drunken Abo.

Confessions of a Headhunter

I must have decapitated ten Queen Victorias, probably twenty Captain Cooks and numerous explorers, botanists, soldiers, founders, anthropologists, archaeologists, men of learning and sundry heroes.

Down by the lake with Phil and Liz

Cement Fondue

Cement fondue was what Greg Taylor used to make his statue of the naked royals, and he coated it with an iron oxide material so it would rust quickly.

Active decay, reminiscent of Dada, was thus built into this work, which in the space of three days, beginning with the decapitation of the Queen, burst into a riveting ‘happening’ at the centre of national attention.

To erect a statue is to take revenge on reality.

Contemptible consideration: Statues have a strategic built-in desire to be violated, without which they are incomplete. Defacement brings inside outside. It fastens onto objects as insects fasten onto leaves.

Money, bronze or a nation’s flag. Defacement of such things brings a very angry god out of hiding. This is the public secret.

“This sculpture has been ceremoniously vandalised” said

Neil Roberts, coordinator of the Canberra National

Sculpture Forum 95.

“But organisers say it will stay. It is more relevant to be left as it is - as a symbol of intolerance,

irrelevance, disintegration.”

Lost places (time): Memorials to places that have disappeared with the passage of time.

Lost places (state): Places that have been removed by official dictate.

“Flag burning,” he stated, “is the equivalent of an inarticulate grunt or roar”.

Police sergeant McQuillan shocked hundreds of tourists as he tried to cover the naked forms of the royal couple with a sheet emblazoned with the Australian flag.

In the first sledgehammer attack on the figurines last week, the Queen’s head was removed; then Prince Phillip was attacked and on Saturday night the Queen’s legs were severed and one of Prince Phillip’s arms was destroyed.

ICONISM

The tendency to “iconism” still exists, even today. ‘Iconism’ is the habit of “selecting”, “choosing”, or “finding” the image that “stands out”, the image that is “the important one”, the image that “says more”, the image that “counts more” than the others. In other words, the tendency to iconism is the tendency to “highlight”; it’s the old,

classical procedure of favouring and imposing,

in an authoritarian way, a hierarchy.

This is not a declaration of importance about something or somebody, but a declaration of importance directed at others. The goal is to establish a common importance, a common weight, a common measure. But iconism and highlighting also have the effect of avoiding the existenceof differences, of the non-iconic and of the non-highlighted. In the field of war and conflict images, this leads to choosing the “acceptable” for others. It’s the “acceptable” image that stands for another image, for all other images, for something else, and perhaps even for a non-image. This image or icon has to be, of course, the correct, the good, the right, the allowed, the chosen -

the consensual image. This is the manipulation.

One example is the icon, much discussed (even by art historians), of the “Situation Room” in Washington during the killing of Bin Laden by the Navy Seals in 2011. I refuse to accept this image as an icon: I refuse its iconism, and I refuse the fact that this image - and all other “icons” - stands for something other than itself. To fight iconism is the reason why looking at images of destroyed bodies is important.

— Thomas Hirschhorn

The authorities announced on the radio that a forensic-psychiatric commission had determined that Kalanta suffered from schizophrenia, but other rumors circulated about the reasons for his death. Some people heard that he had killed himself as a result of a fight with his girlfriend. Others speculated that his death had something to do with the hippies who congregated in the city center.

Local authorities were concerned that the funeral, the time and date of which was evidently known by the inhabitants of Kaunas, would attract attention and took action to prevent it from becoming a public event. During the week, Party activists engaged in “explanatory work” designed to promote the “correct appraisal” of Kalanta’s death. Men in suits came to classrooms in secondary schools throughout the city and warned the young people to stay away from the site of Kalanta’s self-immolation in the city center. They emphasized that the young man who had killed himself was mentally ill and that there was no reason to attempt to attend his funeral.

In the days after Kalanta’s suicide, the authorities increased their presence on the streets. Police and Komsomol brigades patrolled Laisvės Alėja. In the square in front of the Musical Theater, men in plainclothes – assumed to be KGB agents – watched everyone who came by. Official concern of a sympathetic public response was not unfounded. Throughout the week, people attempted to lay flowers at the site of Kalanta’s self-immolation. KGB officials and police officers immediately removed any flowers left on the site.

KAUNAS, MAY 18-19 1960

Despite limited public information about the young man who had set himself on fire in front of the Musical Theater on Sunday afternoon, word of his act spread through the city of Kaunas. People talked about it in their workplaces, in schoolyards and on city buses. Kalanta’s funeral was scheduled for Thursday afternoon, four days after his self-immolation.

We are troubled by our own complicity but we do not speak because we know that “without such shared secrets any and all social institutions – workplace marketplace, state and family – would founder. […] Wherever there is power there is secrecy, except it is not only secrecy that lies at the core of power, but public secrecy.” The public perception of justice – the figure of its appearance – relies on the public not acknowledging that which is generally known. Stolen elections, illegal wars, and state violence could be described as “unknown knowns” – the unstated fourth term of Donald Rumsfeld’s “redundant formulations.”

As we know, There are known knowns.

There are things we know we know.

We also know

There are known unknowns.

That is to say

We know there are some things

We do not know.

But there are also unknown unknowns,

The ones we don’t know

We don’t know.

Donald Rumsfeld – Feb. 12, 2002, Department of Defense news briefing

Logically, Rumsfeld failed to mention “unknown knowns” – the things we know but won’t know we know, the public secrets.

WHAT IS KNOWN

Secrets are the opposite of information. There are secrets that are kept from the public and then there are “public secrets” – secrets that the public chooses to keep safe from itself, like, “don’t ask, don’t tell.” The injustices of the war on drugs, the criminal justice system, and the Prison Industrial Complex are “public secrets”.

The public perception of justice - the figure of its appearance - relies on the public not acknowledging that, which is generally known. When faced with massive sociological phenomena such as racism, poverty, addiction, abuse, it is easy to slip into denial. This is the ideological work that the prison does. It allows us to avoid the ethical by relying on the juridical. The trick to the public secret is in knowing what not to know. This is the most powerful form of social knowledge. Such shared secrets sustain social and political institutions.

“[K]nowing what not to know lies at the heart of a vast range of social powers …the clumsy hybrid of power/knowledge comes at last into meaningful focus, it being not that knowledge is power but rather that active not-knowing makes it so.” We fall silent, slip into denial, when faced with massive sociological phenomenon such as racism, poverty, addiction, abuse, torture, or economic and political forces like globalization, privatization, and militarization.

Recorded onto Celluloid, Absorbed Into Memory: Confessions of a Makeup Artist.

(edited script taken from Permanent Shadows, a commemorative performance by Irwan Ahmett and Subarkah Hadisarjana)

My name is Subarkah. Although I am a makeup artist now, I started off as a painter. For me, make-up, dressing up and other forms of disguise are not so different from conveying the narration of history; accepted in lens, recorded into celluloid then absorbed into memory… becoming a permanent shadow for all who see it.

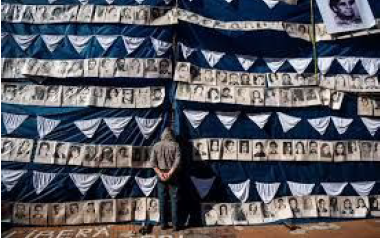

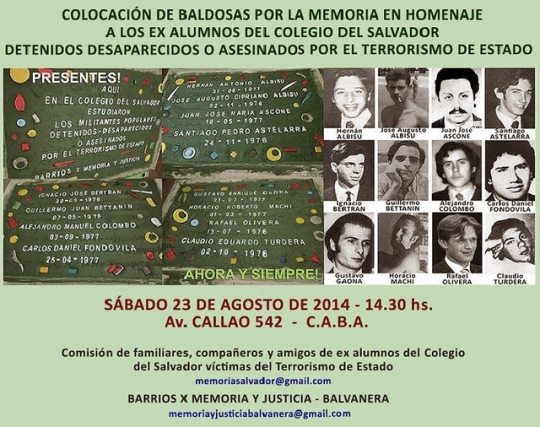

Otro govierno, misma impunidad means “different government, same impunity.” Each claim has been backed by performative evidence—the placards with the photo IDs, the list of atrocities, the identity of repressors

Much as the Abuelas relied on DNA testing to confirm the lineages broken by the military, they and the Madres continue to use photo IDs of their missing children as yet another way to establish “truth” and lineage. This representational practice of linking the scientific and performative claim is what I call the “DNA of performance.”

What does the performative proof accomplish that the scientific cannot achieve on its own?

How does this representational practice lay a foundation for movements that will come after it?

The embodied performative dimension of these protests was as important as the scientific evidence because it brought attention to the national tragedy in the first place. Abuelas and Madres performed the proof. On a state level, human rights trials and commissions, such as Argentina’s National Commission on the Disappeared (which issued Nunca Ma´s [1986] to report its findings) or South Africa’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission, understand the importance of live hearings in making citizens feel like co-owners of the country’s traumatic past. In-between and overlapping systems of knowledge and memory constitute a vast spectrum that might combine the workings of the “permanent” and the “ephemeral” in different ways. Each system of containing and transmitting knowledge exceeds the limitations of the other. The “live” can never be contained in the “archive”; the archive endures beyond the limits of the live.

DNA functions as a biological “archive” of sorts, storing and transmitting the codes that mark the specificity of our existence both as a species and as individuals. Yet it also belongs to the human-made archive, forensic or otherwise. This human-made archive maintains what is perceived as a lasting core—records, documents, photographs, literary texts, police files, fingerprint and DNA evidence, digital materials, archaeological remains, bones—supposedly resistant to change and political manipulation. What changes, over time, the archive maintains, is the value, relevance, or meaning of the remains—how they get interpreted, even embodied.

The scientific, archival “evidence” of DNA offered by the Abuelas was clearly central to their strategy of tracing their loved ones while accusing the military of their disappearance. Testimonial transfers and performance protest, on the other hand, are two forms of expressive social behavior that belong to the discursive workings of what I have called the “repertoire.” The repertoire stores and enacts “embodied” memory—the traumatic or cathartic “shudder,” gestures, orality movement, dance,song—in short, all those acts usually thought of as “live,” ephemeral, non-reproducible knowledge. The embodied experience and transmission of traumatic memory—the interactions among people in the here and now—make a difference in the way that knowledge is transmitted and incorporated. The type of interaction might range from the individual (one-on-one psychoanalytic session) to the group or state level (demonstrations, human rights trials).

Week after week in the Plaza de Mayo, the Madres accused the military of disappearing their children and demanded that they be returned alive (aparicio´n con vida). After the worst moment of military violence passed, Abuelas and Madres started carrying a huge banner in front of them as they walked around the Plaza. With the return to democracy in 1983, they began to accuse the new government of granting impunity to the criminals.

Using loudspeakers, they continued to bring charges, naming their children and naming those responsible for abducting them. They called the Plaza their own, and inscribed their emblematic scarves in white paint around the perimeter.

Even now, they continue their condemnation of the government’s complacency in regard to the human rights abuses committed during the Dirty War .

Each Thursday afternoon, for the past 25 years, the women have met in Plaza de Mayo to repeat their show of loss and political resolve. At first, at the height of the military violence, 14 women walked around the Plaza two-by-two, arm in-arm, to avoid prohibitions against public meetings. Though ignored by the dictatorship, the women’s idea of meeting in the square caught on throughout the country. Before long, hundreds of women from around Argentina converged in the Plaza de Mayo in spite of the increasing military violence directed against them (see Taylor 1997:186–189). Ritualistically, they walked around this square, located in the heart of Argentina’s political and financial center. Turning their bodies into billboards, they used them as conduits of memory. They literally wore the photo IDs that had been erased from official archives.

_______________

On the Madres del Plaza de Mayo: Argentina’s mothers of the disappeared:

from The DNA of Performance by Diana Taylor

The spectacle of elderly women in white head scarves carrying huge placards with photo IDs of their missing children has become an international icon of human rights and women’s resistance movements. By turning their “interrupted mourning process” into “one of the most visible political discourses of resistance to terror” (Sua´rez-Orozco 1991:491) the Abuelas and Madres introduced a model of trauma-driven performance protest.

Secrets that the public chooses to keep safe from itself. The secretly familiar. The sayable unsayable.

Public secrecy becomes a principal arm of wise governance; the hegemon’s infrastructure. For example, a classroom with a curtain running down the middle.

Every secret is explosive, expanding with its own inner heart.

The public secret is also an ingrained poetry of daily habit. It has to be spoken in order to preserve it. We make facades for the secret. It is unmasked so as to preserve it. Depth becomes surface in order to remain depth.

Piotr S

Click here to read more on the public secret

Defacement: Public Secrecy and the Labour of the Negative. Click here to access.

Against official narratives.

This Watch This Space

discursive noticeboard operates

as a space for artists,

researchers, autodidacts and

amateurs to share the matters,

insights, and methodologies

that they think are most urgently needed in the world.

These may take the form of

research or creative works-in

progress. ‘Curators’ of the

noticeboard are expected to

work with a mixture of love,

hope, and urgency to produce a

social space through which to

address, and be addressed by,

others.

Each curator is responsible for providing content to be

wheatpasted onto the

noticeboard over the course of six weeks.

The

noticeboard is intended both to

intervene locally in Alice Springs, and connect local

dynamics with narratives

specific to other places and

people.

The Writing on the Wall

Lanne's skull and body were never reunited. They were guarded jealously by the respective mutilators in the interests of science.

Colonial Headhunter

SCROLL DOWN TO SEE THE

DIFFERENT INSTALLATIONS AND ITERATIONS

OF THE WRITING ON THE WALL, OR READ THEM BY SCROLLING

TO YOUR RIGHT.

Jorgen

Doyle &

Hannah Ekin

-

October

2017

Beth Sometimes - March 2018

As part her residency at Watch This Space Phoebe Beard created a series of artworks based on her research into mineral exploitation in the Northern Territory. Using printed maps as stimulus Phoebe Beard located gold, magnesium, copper and uranium mines outside Alice Springs/Mparntwe. As a printmaker Phoebe held a series of workshops called ‘X Marks the Spot’ which granted participants with the opportunity to create their own personalised map or brochure. Phoebe Beard utilised the Watch This Space notice board to display and distribute her printed maps, to which indicated the economic and environmental impact of mineral exploitation in the Northern Territory Australia.

My research into the once known gold rush town of Arltunga 110km east of Mparntwe/Alice Springs has inspired this lino cut which describes the act of fossicking on the left. Arltunga, occupied by the east Aranda people was the first European settlement in Central Australia. Gold was said to be found in the area in 1887, transforming Arltunga into a mining hub. The one layer lino cut describes the process of fossicking and its contribution to industrialisation in Australia.

PHOEBE BEARD

SEP 2018

Maximise your browser and zoom out to 25% while choosing your noticeboard installation of choice and then zoom in until it takes up the height of your screen.

HARRY COPAS

OCT 2018